Table of Contents

- 6.1 Overview

- 6.2 Assessing Evidence at the Key Question and Linkage Levels

- 6.3 Dealing With Intermediate, Secondary, and Composite Outcomes

- 6.4 Determining the Adequacy for Benefits and Harms Linkages

- 6.5 Assessing Magnitude of Benefit

- 6.6 Assessing Magnitude of Harm

- 6.7 Assessing Certainty of Evidence for the Entire Analytic Framework

- 6.8 Assessing Magnitude of Net Benefit

6.1 Overview

The preceding sections have described the processes for systematic evidence reviews and related reports that serve as the foundation for Task Force recommendations. This section briefly describes the specific work of the Task Force in examining and judging the cumulative evidence and making recommendations. Further details about the Task Force's methods can be found in a series of published articles (Section 10).

The Task Force's steps to arrive at a recommendation include:

- Assessing the adequacy of evidence at the key question level.

- Assessing the adequacy of evidence at the linkage level.

- Estimating the magnitude of benefit and harm of the preventive service.

- Evaluating the certainty of the evidence for net benefit for the preventive service.

- Estimating the magnitude of the net benefit of the preventive service.

- Developing a recommendation grade for the preventive service in the relevant population, based on the above parameters.

Once the admissible evidence has been gathered and the internal and external validity of individual studies has been assessed by the EPC review team, the Task Force evaluates the adequacy of evidence that the studies provide toward answering the key questions and addressing the linkages in the analytic framework. The evidence addressing a linkage in an analytic framework may come from more than one key question. For example, to assess the benefit of an intervention (linkage), key questions may need to be answered about the 1) effect of different intervention types (e.g., behavioral counseling, pharmacotherapy), 2) effect of intervention timing, and 3) health outcomes in different subpopulations. The USPSTF often uses a tool structured by key question to help facilitate its discussions and organize its assessment of the adequacy of the evidence and the certainty and magnitude of the net benefit (Appendix XI).

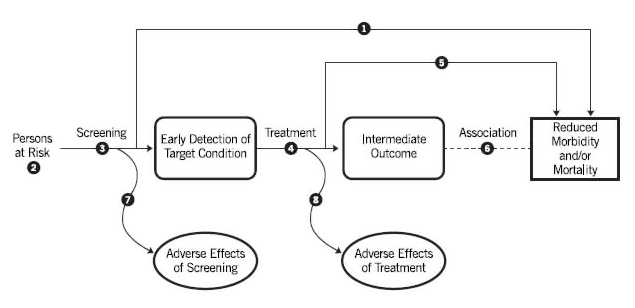

Direct evidence linking clinical preventive services to outcomes is often inadequate either because of a lack of direct evidence or because of limitations in the direct evidence that is available. Thus, the Task Force often needs to use indirect evidence in making its recommendations. This requires assessing the evidence related to the linkages in the chain of evidence between the preventive service and outcomes. For example, the linkage in the chain of evidence for screening usually includes key questions about the accuracy of screening tests, the efficacy and harms of early treatment, and the association between changes in intermediate measures due to specific interventions and changes in health outcomes.

The Task Force's process for determining the adequacy of evidence for a key question or across a linkage in the analytic framework involves answering six critical appraisal questions about the admissible evidence (Table 2).

Table 2. Factors Considered for Evaluating Adequacy of Evidence for Key Questions (Critical Appraisal Questions)

| 1. Do the studies have the appropriate research design to answer the key question(s)? 2. To what extent are the existing studies of sufficient quality (i.e., what is the internal validity)? 3. To what extent are the results of the studies generalizable to the general U.S. primary care population of interest to the intervention and situation (i.e., what is the applicability)? 4. How many and how large are the studies that address the key question(s)? Are the results precise? 5. How consistent are the results of the studies? 6. Are there additional factors that assist us in drawing conclusions (e.g., fit within a biological model)? |

6.2 Assessing Evidence at the Key Question and Linkage Levels

6.2.1 Ratings of Adequacy for Key Questions

The Task Force rates the body of evidence for each key question as convincing, adequate, or inadequate.

6.2.1.1 Internal and External Validity

In making a determination of adequacy, the Task Force considers the aggregate internal and external validity of all studies across each of the key questions. The determination is based on a careful consideration of the studies that are judged as fair or good quality, using criteria based on each type of study design, in a body of evidence. The EPC develops its evidence appraisal for each key question based only on studies with strong internal and external validity by including studies that are potentially relevant to the U.S. primary care population, settings, and providers (Appendix VII). The EPC displays factors related to applicability in its summary of evidence table for use by the USPSTF.

6.2.1.2 Other Factors to Consider

The Task Force also considers other important factors in addition to internal and external validity to judge the adequacy of evidence for each key question: the number and heterogeneity (statistical and/or clinical) of studies for each key question, the consistency and precision of reported outcomes, and other factors that appear to strengthen inferences about causal relationships.

6.2.1.3 Criteria for Ratings

Evidence for a key question may be deemed "convincing" when there are sufficient well-conducted studies of appropriate design that demonstrate consistent and precise results focused on outcomes and generalizable to the intended U.S. primary care population and setting. The consistency of or a large number of individual studies and lack of heterogeneity in pooled results strengthens the case for the evidence to be deemed convincing. The Task Force assesses the consistency of the evidence addressing a key question by examining the degree to which studies demonstrate similar directionality and magnitude of results. When statistical or clinical heterogeneity is present, the Task Force evaluates the comparability of studies with regard to study design, patients/subjects, interventions, comparators, settings, and outcomes to determine the coherence of evidence.

Evidence for a key question may be deemed as "adequate" when the evidence is sufficient to answer a key question, but is less convincing because of one of more significant limitations in factors, such as the appropriateness of study design, quality of studies, applicability of results, overall precision, and/or heterogeneity of evidence.

Evidence for a key question may be deemed as "inadequate" when evidence is insufficient to answer a key question because of a complete lack of evidence or a fatal flaw in one or more of the following factors: consistency of results, precision, applicability, and/or study quality and design. Inadequate evidence (for either benefits or harms) may create a critical gap in the evidence chain.

6.3 Dealing With Intermediate, Secondary, and Composite Outcomes

6.3.1 Intermediate Outcomes

The need to evaluate the evidence for the key question linking intermediate to health outcomes (Key Question 6 in Figure 4) in order to make a recommendation will depend on the overall body of evidence. The Task Force may consider the evidence linking intermediate and health outcomes (Key Question 6) when there is inadequate direct evidence (Key Question 1) and inadequate evidence linking earlier treatment to health outcomes (Key Question 5). The process for determining the adequacy of the evidence for the key question (Key Question 6) on the link between intermediate and health outcomes is similar to the process for other key questions, as described above in Sections 6.2 and 6.4, but additionally requires special considerations, as discussed below. These considerations are necessary, given the unique characteristics of relationships between intermediate and health outcomes and because of the added potential threat to the certainty of the evidence that this additional link creates.

As discussed in Sections 6.2 and 6.4, the adequacy of the evidence depends on the availability of well-conducted studies of appropriate design that demonstrate consistent and precise results focused on outcomes that are generalizable to the intended U.S. primary care population and setting. The consistency of, or a large number of, individual studies using the same intermediate and health outcomes strengthens the case for the evidence to be deemed convincing. As with other types of key questions and linkages, the Task Force assesses the consistency of the evidence by examining the degree to which studies demonstrate similar directionality and magnitude of results.

The ultimate goal for assessing the evidence for this key question is to determine precisely a consistent relationship between the direction and magnitude of change in an intermediate outcome with a predictable resultant direction and magnitude of change in the health outcomes. Acceptable evidence may come from posttrial data that follows subjects over time to determine the effect of an intervention or treatment on intermediate and health outcomes. When trial data are not available to answer this key question, the Task Force may consider observational evidence that provides epidemiological support for causation. In addition, cohort studies that follow subjects over time and report changes in intermediate and health outcomes may be considered. Added strength may come from evidence that shows similar magnitude of effect on multiple intermediate and health outcomes. When statistical, methodological, or clinical heterogeneity is present in the body of evidence for this link, the Task Force evaluates the comparability of studies with regard to study design, patients/subjects, interventions, comparators, settings, and outcomes to determine the coherence of evidence. This is of particular importance in this key question.

The Task Force will exercise great caution when making a recommendation that depends in large part on the evidence linking intermediate and health outcomes. Due to the inherent limitations of the evidence that will be used to link intermediate and health outcomes, it is very unlikely that the evidence for this key question will be deemed convincing. This is due to the likely need to depend on observational evidence and the high potential for confounding. It is important to emphasize that strong associations between intermediate and health outcomes that are based only on cross-sectional studies would likely not be deemed adequate evidence for this key question. Evidence for this key question may be deemed as "adequate" (but not convincing) when the evidence is sufficient to answer the key question, but is less convincing because of one or more significant limitations, such as the appropriateness of study design, quality of studies, number and size of studies, applicability of results, overall precision, and/or heterogeneity of evidence (as discussed above).

Figure 4 . Template of an Analytic Framework

6.3.2 Dealing With Secondary and Composite Outcomes

The Task Force adopted a policy of critically appraising all the endpoints (outcomes) of trials in a similar manner, following the six critical appraisal questions in Table 2. In its review, the Task Force takes note of the biological plausibility of a study's finding, the supporting evidence, and whether an outcome is a primary or secondary one. Similarly, the Task Force examines composite (aggregate) outcomes carefully. It generally asks three questions of these outcomes: 1) Are the component outcomes of similar importance to patients? 2) Did the more or less important outcomes occur with similar frequency? and 3) Are the component outcomes likely to have similar relative risk reduction?

6.4 Determining the Adequacy for Benefits and Harms Linkages

After assessing the adequacy of the evidence at the key question level, the USPSTF assesses the adequacy of the evidence across the linkages. A linkage is represented by an arrow or a combination of arrows in the analytic framework that links the population on the left side of the framework to the beneficial or harmful health outcomes on the right side of the framework. Each linkage may be evaluated by one or more key questions. For example, in a cancer screening recommendation, the "benefit linkage" connects the population of asymptomatic adults without known cancer to the potential benefit of a reduction in mortality. This linkage could be evaluated by the following key questions, in combination: 1) Does screening reduce mortality? 2) Does early treatment of asymptomatic adults reduce early markers? 3) Does early treatment of asymptomatic adults reduce mortality? and 5) Do changes in these early markers lead to improvements in health outcomes and/or reduced mortality? Evidence from key questions on risk assessment and/or detection may also inform the assessment of the evidence on the benefit (or harm) linkage. The evidence on an overall linkage is classified into one of three categories: convincing, adequate, or inadequate.

Adequacy of the linkage for benefits or harms is not a simple summation of the adequacy for the key questions, but is determined by consideration of the six critical appraisal questions (Table 2), the coherence across all the evidence for the linkage, and other considerations, as described below.

Coherence is used (in addition to consistency) to indicate that a body of evidence "makes sense," in that it fits together to present an understandable picture of the benefit of a preventive service in an asymptomatic U.S. primary care population. It includes an assessment of the concordance between populations, interventions, and outcomes in the studies reviewed. Several studies of a preventive service may find different results (and thus be inconsistent), but the results may still be understandable (and thus coherent) in terms of the populations studied or the interventions used.

As part of coherence, USPSTF members assess the applicability of the body of evidence to populations, situations, providers, and settings as one of the components of the overall linkage. Judgment about applicability considers these factors but also involves synthesis of the evidence from the individual studies across the key questions and for the overall body of evidence for a linkage. The goal of the assessment is to judge whether there are likely to be clinically important differences between the observed body of evidence and the results expected when the intervention is implemented among asymptomatic patients in U.S. primary care settings, populations, and providers.

The following concepts are used to understand the applicability of the body of evidence to preventive interventions in an asymptomatic, primary care population in the United States:

- Inferences from the evidence that the intervention has effectiveness for U.S. primary care populations, situations, and providers.

- The magnitude of benefit or harm observed in individual studies that comprise the body of evidence compared with the expected magnitude in the U.S. primary care setting.

- The applicability of the information on benefits and harms in individual studies that comprise the body of evidence to understanding the expected benefits and harms in U.S. primary care settings and populations.

- Information on the acceptability, feasibility, and availability of the studied intervention in U.S. primary care populations and settings.

- Biological plausibility and clinical relevance of extrapolating from the body of evidence to large populations of asymptomatic persons in a primary care setting.

Extrapolation is used by the Task Force to make inferences across the analytic framework to complete a chain of evidence connecting the intervention with health benefits. The Task Force extrapolates from existing evidence only when the case for doing so is strong. In these cases, the Task Force is not considering the question of whether a study applies to a different population, situation, or provider. Instead, it is judging whether a gap in the evidence within the analytic framework can be overcome with epidemiological evidence, logic and biological plausibility. Two factors—logic and biological plausibility—play the greatest role in the decision about extrapolation.

When extrapolation is used to reach a letter grade recommendation, the scientific rationale for the recommendations and the methods used to review and judge the evidence are explicitly stated along with the recommendations. Examples of such consideration include whether the Task Force can: 1) extrapolate evidence about intermediate outcomes to health-related outcomes, 2) infer long-term health outcomes based on shorter-term outcomes, and 3) infer the effects of population-based screening based on RCTs of treatment of selected patients identified through case-finding.

6.4.1 Other Considerations for Determining the Adequacy of Evidence for Linkage: Benefits

The adequacy of the evidence for benefits may be further limited or strengthened by the following considerations:

- The availability of evidence on the effectiveness of early treatment compared with later treatment (or when the condition is asymptomatic vs. clinically apparent) of the subtype of the condition that would cause health problems.

- Evidence on the prevalence or natural history of the target condition, or for heterogeneous conditions, evidence on the prevalence of the subtype of the condition that would cause important health problems.

- For screening, the sensitivity and expected positive predictive value of the screening test (i.e., the degree to which the test will detect the subtype of the condition that would potentially cause health problems).

- Evidence showing a statistically significant effect but limited or unknown clinical importance.

- Lack of evidence on important health outcomes.

- Applicability of included studies to the screen-detected, asymptomatic, primary care, U.S. population.

- Inability to ascertain the precise combination of factors and the risk threshold necessary to identify the target population for the preventive intervention; this happens when recommendations are made for high-risk populations that are identified largely based on one or more risk factors for a condition, but no multivariable risk prediction tools are available.

- Evidence on well-established, evidence-based benefits for key questions (often addressed in previous USPSTF reviews) (i.e., "foundational evidence").

6.4.2 Other Considerations for Determining the Adequacy of Evidence for Linkage: Harms

The adequacy of the evidence for harms may be further strengthened or limited by the following considerations:

- Information on the severity of harms, including patients' perspectives on the acceptability of specific harms

- What is known about the number of false-positives, the invasiveness of the diagnostic workup, and the expected amount of overdiagnosis and overtreatment

- Prevalence and severity of disease

- Timing between screening test and confirmatory/diagnostic testing and/or treatment

- Evidence on well-established, evidence-based harms for key questions (often addressed in previous USPSTF reviews)

After careful deliberation, the Task Force determines how all the evidence and considerations are coherent; that is, it "make sense" in assessing if there is enough information to determine an overall benefit or harm and whether the Task Force can determine its magnitude (see below for more information about assessing magnitude). Therefore, the overall benefit linkage can be determined to be inadequate by the Task Force even though there is adequate evidence for the individual key questions related to benefits because of the limitations discussed above. One example is screening for cognitive impairment, in which there was adequate evidence that some interventions resulted in improvements in some measures of beneficial outcomes, but the overall evidence for the benefit linkage was determined to be inadequate because 1) there was limited evidence that these changes resulted in clinically significant benefits, and 2) there was a lack of data on important outcomes (i.e., decisionmaking by patients and their families). These situations can occur because coherence, based on the six critical appraisal questions (Table 2) and other considerations, strengthens or limits the adequacy of the evidence above or below the actual evidence for individual key questions. How the Task Force uses the impact of these considerations on evidence adequacy to "bound" the magnitude of benefits or harms is discussed below.

6.4.3 Reaffirmations

The USPSTF may reaffirm a previous grade A or D recommendation. These are well established, current, evidence-based practices in primary care for which only a very high level of evidence would justify a change in the grade of the recommendation (e.g., screening for hypertension). In determining the adequacy of evidence for the benefits and harms linkages, the USPSTF considers whether the new evidence is of sufficient strength and quality to change its previous assessment of the certainty of the evidence. If the USPSTF does not find evidence of sufficient strength and quality to change its previous assessment, the USPSTF may vote to reaffirm the previous recommendation, using its usual voting procedure. A draft reaffirmation statement is prepared for consideration that includes a summary statement of the recommendation and evidence, the rationale, updated clinical considerations, and a brief summary of the systematic review or evidence update, with references to both the current evidence update and the previous systematic review. The draft reaffirmation statement is posted for public comment following the usual process. The newly dated reaffirmation statement, a link to the previous evidence review and recommendation statement, and the summary of the evidence are made available on the USPSTF Web site following usual processes.

6.5 Assessing Magnitude of Benefit

6.5.1 Definitions of Magnitude Ratings and Criteria

In situations where the evidence is adequate or convincing for benefit, the Task Force considers all the admissible evidence to determine the magnitude of benefit that would be expected from implementing the preventive service in a defined population. The magnitude of benefit is categorized as substantial, moderate, small, or zero. If the evidence is deemed inadequate for the assessment, the magnitude of benefit rating is not applicable. The Task Force uses the evidence to estimate the size of the population that would benefit from implementation of the preventive service over a given time horizon (appropriate to the service under consideration) and over the expected time to benefit. Specific health benefits might include such outcomes as overall mortality reduction, clinically meaningful improvements in health-related quality of life, or avoidance of specific disease events (e.g., cardiovascular events, cancer incidence and mortality, visual impairment, complications from alcohol use).

6.5.2 Determining Magnitude of Benefit Across the Analytic Framework

For some services, benefits can be estimated directly from large well-conducted RCTs of preventive services, with specific health benefits as prespecified outcomes and conducted in participants representative of the population under consideration. More commonly, however, this direct evidence is not available and the Task Force must assess the evidence across the key questions and the linkages in the analytic framework. For example, if an RCT of screening is not available, evidence may be assessed related to the accuracy of the screening test and the benefits of treatment in a screened population, and may include studies examining intermediate or final health outcomes. This indirect method of determining magnitude of benefit requires more assumptions and thus is associated with greater uncertainty than when direct evidence is available. In general, evidence derived from well-conducted trials evaluating a preventive service is likely to have more certainty than evidence from indirect assessment across key questions and linkages between intermediate and final health outcomes.

The Task Force examines both relative risk reduction (RRR) and absolute risk reduction (ARR) from intervention studies. It generally prioritizes ARR over RRR. That is, it places less emphasis on a large RRR in situations of low ARR; it remains interested in an intervention with a low RRR if its ARR is high. Even a low ARR may be important for critical outcomes (e.g., mortality).

6.5.3 General Considerations for Determining Limits on Magnitude of Benefit

Estimates of magnitude of benefit are meant to describe the amount of the burden of suffering from the condition (within a stated population) that can be expected to be prevented by the intervention in question. The magnitude of benefit cannot be greater than the total burden of suffering.

For preventive interventions, the population benefit may be further limited by such issues as the following:

- The prevalence and incidence of the target condition.

- For heterogeneous conditions, the prevalence of the condition subtype that would cause important health problems.

- The sensitivity of the screening test (i.e., the degree to which the test or a given threshold to define abnormality of the screening test will detect the subtype of the condition that would potentially cause health problems; sensitivity is rarely 100%).

- The comparative effectiveness of early treatment of asymptomatic disease relative to later treatment of symptomatic disease of the subtype of the condition that would cause health problems (rarely 100%).

6.5.4 Conceptual Confidence Limits

As previously noted, estimates of magnitude of benefit are intrinsically more uncertain when direct evidence is limited or absent or restricted to select populations or clinical scenarios. In these cases, the Task Force may place conceptual upper or lower bounds on the magnitude of benefit as applied to the population targeted in the recommendation. Considerations such as baseline risk of study participants and the clinical setting in which the studies were conducted also factor into the bounds of estimates of magnitude of benefit. For example, if magnitude of benefit is estimated only from studies of an intervention conducted by highly trained clinicians using specialized equipment for persons at considerably increased risk, this estimate might be considered the upper bound for benefit that might reasonably be anticipated for a general population. In other situations, the Task Force may also logically judge the lower bounds of the benefit, particularly when estimating the anticipated benefits in a population with a lower prevalence of disease than the study population in which the estimate of the benefit was derived.

Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm is an example of the Task Force's use of conceptual confidence intervals. The benefits observed in screening studies of male smokers that were conducted in academic centers with optimal diagnostic and surgical treatment capabilities were judged to likely represent the upper bounds of benefit if these services were to be provided more generally in community-based settings. A lower conceptual bound of potential benefit was judged when extrapolating these studies in a high-risk population (male smokers) to populations at lower risk (male nonsmokers and female smokers and nonsmokers).

6.5.5 Outcomes Tables and Decision Modeling for Determining Magnitude of Benefit

One way to determine the magnitude of benefit is to use an outcomes table based on the systematic evidence review or, when available, outputs from a decision model. An outcomes table can demonstrate how many or the proportion of persons likely to benefit—and in what ways—from implementation of the preventive service. Estimates from direct and indirect evidence may be included in outcomes tables in order to provide the range of expected magnitude of specific beneficial outcomes (Appendix VIII).

6.6 Assessing Magnitude of Harm

6.6.1 Definitions of Magnitude Ratings and Criteria

The Task Force starts with the conceptual notion that screening, counseling, or use of preventive medications are intended for asymptomatic individuals in order to prevent or delay future health problems. The burden of proof that the benefits exceed the harms prior to recommending implementation of screening or other preventive services is thus higher than it is for diagnosis or treatment of symptomatic conditions. As such, assessment of the magnitude of harm is critically important. As with the magnitude of benefit, in situations where the evidence is adequate or convincing for harm, the magnitude of harm is assessed using the following categories: substantial, moderate, small, or zero. If the evidence is deemed inadequate for the assessment, the magnitude of harm rating is not applicable.

The Task Force uses the evidence to estimate the size of the population that would be harmed from implementation of the preventive service over a given time horizon (appropriate to the service under consideration) and over the expected time to be harmed and the duration/severity of the harm. Assessment of the magnitude of harm may be more difficult than assessment of benefit for many reasons. The broad range of potential harms is often less well identified or reported than potential benefits. At times severe harms occur at a relatively infrequent rate compared to benefits and require larger sample sizes than those studied in RCTs designed to evaluate benefits. Unlike fairly discrete benefits that the preventive service is intended to provide, harms are often varied and complex, occur at several stages in the screening cascade (including at earlier times than for benefits), may persist, and may be poorly recognized. Furthermore, for many, understanding that screening and preventive tests and procedures can cause harm is conceptually difficult.

As with benefit, the magnitude of harm might be determined directly from the reported results of large well-conducted RCTs of a preventive intervention, but more often also requires an assessment across the key questions and the linkages in the analytic framework (even when RCTs are available). Nonrandomized studies are often considered a more reliable source of detecting and determining the magnitude of harm (especially rare but serious harms) than for assessment of benefit. Data on harms may be inadequate for an assessment of magnitude, even when there is adequate data to characterize benefit because of the variability in the reporting of harms and the fact that many studies are not statistically powered or designed to detect some harms.

6.6.2 General Types of Harm for Consideration

The Task Force starts with the assumption that nearly all preventive interventions have the potential to result in some magnitude of one or more harms to patients. For screening-based recommendations, the Task Force looks for harms of the screening test, the subsequent diagnostic tests resulting from screening, and early treatment of screen-detected asymptomatic disease. For recommendations that involve preventive medications and behavioral interventions, the Task Force looks at the magnitude of harm from these interventions.

Harms of screening may include psychological harm from labeling, the harms of diagnostic studies to confirm the presence of the condition, and overdiagnosis of screen-detected conditions. Because screening and other preventive interventions are implemented in asymptomatic persons with the goal of preventing future disease, the Task Force places a high priority on the effects of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, whereby the preventive service has the unintended consequence of creating "disease" that often leads to unnecessary and ineffective treatment. Harms of early treatment and overdiagnosis may accrue to patients whose condition might never have come to clinical attention or for whom the harms of treatment initiated prior to routine clinical detection were different or occurred earlier and/or over a longer period of time. In other words, these are harms of treatment that would not have occurred in the absence of screening.

Harms may also be considered in the form of opportunity costs for both patients and providers. The Task Force may consider the time and effort required by both patients and the health care system to implement the preventive care service. If the time and effort are judged to be substantially greater than other preventive services delivered in the primary care setting, these factors are also considered in the harms category. The Task Force usually derives qualitative, rather than precise, estimates of opportunity costs.

Although opportunity costs may be considered in the determination of Task Force recommendation grades, financial costs are not. Financial costs are also not considered in the decision models used for Task Force recommendations.

6.6.3 Conceptual Confidence Intervals in Face of Inadequate Direct Evidence of Harms

Although there is often less evidence about potential harms than about potential benefits, the Task Force may draw general conclusions from evidence on expected yield of screening in terms of false-positive test results. If the prevalence of the condition is low and the specificity of the test is less than 100%, the positive predictive value may be low and false-positive test results will be expected. If the diagnostic workup is invasive or otherwise carries clinically important potential for harm, the Task Force can infer that at least some harms will result from implementation of the screening program, because some persons with false-positive screening tests will undergo an invasive diagnostic protocol for no possible benefit.

Similarly, if overdiagnosis (and therefore overtreatment) is common, and if the treatment has some adverse effects, the Task Force may infer that implementation of routine screening will cause at least some incremental harms, even in the absence of studies that characterize harms. This approach does not require an exact estimate of the magnitude of harm, but rather a determination that the harms are unlikely to be less than what is known about the number of false-positives, the invasiveness of the diagnostic workup, and the expected amount of overtreatment. Care should be taken to call attention to the estimate's lack of precision.

6.6.4 Presentation of Harms in Outcomes Tables

As with the magnitude of benefit, the magnitude of harm may be informed by an outcomes table based on the systematic review or, when available, outputs from a decision model. When outcomes tables are used to present benefits, estimates for harms will also always be presented.

6.7 Assessing Certainty of Evidence for the Entire Analytic Framework

6.7.1 Overview

The Task Force defines certainty as "likelihood that the USPSTF assessment of the net benefit of a preventive service is correct." The net benefit is defined as the benefits minus the harms of the preventive service as implemented in a general primary care population. The USPSTF assigns a certainty level based on the nature of the overall evidence available to assess the net benefit of a preventive service.

The recommendation grade for a preventive service is derived from separate assessments of the certainty of evidence for a service and the magnitude of net benefit the service offers to persons when performed.

Assessing the certainty of evidence requires a complex synthesis of all evidence across the entire analytic framework. Ultimately, the Task Force rates the certainty of the evidence as one of three categories: high, moderate, or low.

The goal of this assessment is to judge whether the results observed in the individual studies that comprise the body of evidence would be expected when the intervention is delivered to asymptomatic persons by providers in U.S. primary care settings.

6.7.2 Assessment of Certainty of Net Benefit

The Task Force uses multiple sources of information to rate certainty of net benefit, using the criteria listed in Table 3. The evidence review and tables provide much of the data, but the Task Force also uses the information on adequacy derived from the assessment of key questions and linkages (Appendix XI).

The evidence is evaluated for both the direct linkage (generally for Key Question 1) and indirect linkages (involving multiple key questions). The direct pathway is typically derived from RCTs of the targeted screening or preventive intervention that adequately measure the desired health outcomes in the population(s) of interest. This type of evidence is generally associated with higher level of certainty. If certainty for net benefit cannot be derived from the direct pathway, then the Task Force determines if the evidence is sufficient across the key questions and linkages in the indirect pathway to determine overall certainty. If there is a clear gap in the chain of evidence in the indirect pathway (e.g., insufficient evidence for treatment or a screening test), then the certainty across the entire framework is categorized as "low" (Section 6.7).

If there is at least adequate evidence for either the direct or indirect pathway, the Task Force addresses how the body of evidence within the analytic framework fits together to provide an accurate and coherent estimate of the expected magnitude of net benefit (i.e., benefits minus harms) that would be realized from widespread implementation of the preventive service either in the general population or in specific subpopulations. To achieve moderate or high certainty, the Task Force requires that the body of evidence is applicable to asymptomatic persons in the U.S. primary care population, and that the services can be feasibly delivered in U.S. primary care settings or referred to outside resources.

6.7.3 Conceptual Confidence Intervals to Define Certainty Levels

Certainty may also be thought of as the width of the conceptual confidence interval given by the evidence to estimate the magnitude of net benefit. This is not a quantitative calculation, but rather a judgment based on the six critical appraisal questions and how the evidence fits together to complete the linkages from the left side of the analytic framework (population) to the right side (health outcomes). A wide conceptual confidence interval can be due to: lack of evidence about one or more key questions or inadequate evidence to support the linkages; limitations in study design (including inadequate power or poor internal or external validity); too few studies; inconsistency or incoherence of results across studies; or other aspects of the studies that cloud the interpretation of the magnitude of net benefit. When the conceptual confidence interval is wide, the magnitude cannot be estimated with sufficient confidence, and the entire body of evidence is categorized as having low certainty.

When the evidence satisfies most of the six critical appraisal criteria and fits together well enough to make the connections across the analytic framework, the conceptual confidence interval is considered to be narrower. In this case, there is a better (although not precise) estimate of the magnitude of benefit, harm, and net benefit. This type of body of evidence is categorized as having moderate certainty.

When the evidence satisfies each of the six critical appraisal criteria across the analytic framework and the evidence fits together well, the conceptual confidence interval is narrow there is a precise estimate of the magnitude of benefit, harm, and net benefit. In this case, the body of evidence is categorized as having high certainty. Table 3 defines the three certainty levels of the overall evidence.

Table 3. USPSTF Levels of Certainty Regarding Net Benefit

| Level of Certainty | Description |

|---|---|

| High | The available evidence usually includes consistent results from a multitude of well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative primary care populations. These studies assess the effects of the preventive service on the desired health outcomes. Because of the precision of findings, this conclusion is therefore unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies. These recommendations are often based on direct evidence from clinical trials of screening or behavioral interventions. High-quality trials designed as "pragmatic" or "effectiveness" trials are often of greater value in understanding external validity. |

| Moderate | The available evidence is sufficient to determine the effects of the preventive service on targeted health outcomes, but confidence in the estimate is constrained by factors such as:

As more information becomes available, the magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and this change may be large enough to alter the conclusion. |

| Low | The available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes. Evidence is insufficient because of:

More information may allow an estimation of effects on health outcomes. |

The Task Force is careful to assess the certainty of the evidence and the magnitude of benefit, harm, and net benefit separately. For example, the Task Force may have high certainty of the overall evidence and still determine that there is small (or even zero) magnitude of net benefit. The Task Force may also have moderate certainty of the evidence and determine that there is a substantial magnitude of net benefit.

6.7.4 Implementation Considerations When Grading Certainty

The Task Force seeks to make recommendations based on projections of what would be expected from widespread implementation of the preventive service in primary care practice settings across the United States. For this reason, the Task Force carefully considers the applicability to clinical practice of "efficacy" trials, which measure the effects of the preventive care service under ideal circumstances. The Task Force ultimately seeks to weight its recommendations with "effectiveness" trials, which measure the effects of widespread implementation under usual practice circumstances. Such studies are not always available. Therefore, the Task Force attempts to estimate the likelihood that the benefits and harms reported in efficacy studies could be replicated in clinical practice and nonstudy populations. Additionally, the Task Force carefully considers the real-world feasibility of interventions specified in efficacy studies. Some practices have greater support and more resources than others to implement recommended services.

6.8 Assessing Magnitude of Net Benefit

6.8.1 Definitions and Criteria Used to Assess the Magnitude of Net Benefit

To specify the magnitude of the effect of a preventive service, the Task Force separately assesses the magnitude of benefit and harm and then combines these into an assessment of net benefit. The Task Force defines net benefit as the magnitude of the benefit of the service minus the magnitude of the harm. The Task Force gives equal attention to both benefits and harms, since it is well aware that preventive interventions may result in harms as either a direct consequence of the service or for other "downstream" reasons (e.g., diagnostic workup). Furthermore, preventive services are offered to asymptomatic persons. The majority of persons do not benefit from the service, and if they do, the benefit is in the future, often requiring many years to realize. Yet these persons are still subject to harms (often immediate), including opportunity costs.

This initial assessment is first developed by the topic leads after assessing the benefits and harms for each of the key questions and linkages. It is then presented to the full Task Force at the time the draft recommendation statement is deliberated. The Task Force requires the certainty of evidence to be either moderate or high in order to make an assessment on the magnitude of net benefit. If the certainty of the evidence is low, the Task Force is unable to assess the magnitude of net benefit of the preventive service.

The Task Force rates net benefit as substantial, moderate, small, or zero/negative. "Substantial" net benefit indicates that the benefits substantially outweigh the harms, whereas "zero/negative" net benefit indicates that the harms equal or outweigh the benefits.

6.8.2 Metrics and Data Used to Assess the Magnitude of Net Benefit

Weighing the balance of benefits and harms can be challenging, because these outcomes are often measured in different metrics and over different time frames. Benefits are often quantified in terms of lives extended, quality of life improved, or illness events averted. Many of these often take years to achieve and may only accrue to a small percentage of individuals. Harms are often measured using metrics such as the false-positive screening test rate, overdiagnosis, diagnostic tests and their complications, or adverse effects of treatment, some of which are ineffective or unnecessary. Many of these occur more frequently and earlier than benefits. When the body of evidence does not use a single metric common to both benefits and harms, the assessment of net benefit is inherently subjective.

The Task Force attempts to quantify the magnitude of benefit and harm that would result from implementing the preventive service in the general primary care population. One way of doing so is by using such metrics as "number needed to treat" (i.e., NNT, the number of persons who would need to be treated for some defined period of time to prevent one adverse health event) or "number needed to screen" (i.e., NNS, the number of persons who would need to be screened for some defined period of time to prevent one adverse health event). One can also derive a similar "number needed to harm" (i.e., NNH, the number of persons needed to be treated or screened for a defined period of time to cause one adverse health event). Because of the uncertainty and variability in the evidence used to make these estimates, the Task Force does not have a defined threshold for NNT, NNS, or NNH for assessing the magnitude of net benefit.

When results from decision modeling conducted for the Task Force are available, the outputs may specifically inform the assessment of magnitude of net benefit (Section 5). Similarly, an outcomes table generated from a systematic review also outlines the tradeoffs in terms of projected benefits and harms in a population. The Task Force has standardized this outcomes table to the extent possible (Appendix VIII), but there will always be some variation, depending on the topic.

The Task Force does not use specific criteria to differentiate levels of net benefit. Net benefit, as used by the Task Force, is often assessed as substantial in those situations in which either:

- A large proportion of the total burden of suffering from the target condition (minus the additional burden caused by the preventive service) would be relieved from society by implementing the preventive service. This criterion applies even if the target condition is rare.

- A large amount of the burden of suffering would be relieved from society (minus the additional burden caused by the preventive service) by implementing the preventive service.

Note that in both of these situations, a population can be defined that has a substantial burden of suffering from the target condition, even if rare, and there is a prevention strategy that reduces that burden by a substantial amount. Net benefit, however, would only be substantial if the harms of the intervention are zero or small. Thus, both the magnitude of harm and the magnitude of benefit are each critical factors in determining net benefit.

Current as of: July 2017

Internet Citation: Section 6. Methods for Arriving at a Recommendation. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. July 2017.